ELEPHANT STUDY CETRE

(Elephant World Project)

Location: Surin Province,Thailand

Client: Surin Provincial Administrative Organization, Thai Government

Building type: Elephant Playground, Brick Observation Tower, Museum

Project Year: 2015-2020

In the project Elephant World in Thailand’s Surin Province, the architecture attempts to describe unique differences between Thai locals and Thai elephants compared to the relationships between man and elephant found in other cultures. The elephant is considered a part of the human family structure, and as a result, is one of the tamest of all elephants in the world due to their close emotional ties to their human caretakers. Therefore, Elephant World isn’t viewed as a collection of cages for undomesticated animals, but rather large residence for one of the human family members.

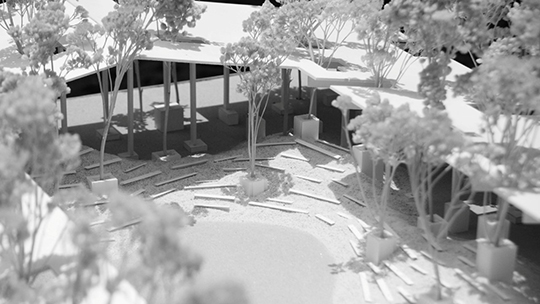

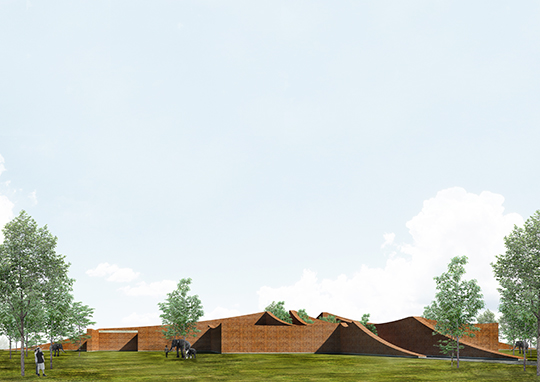

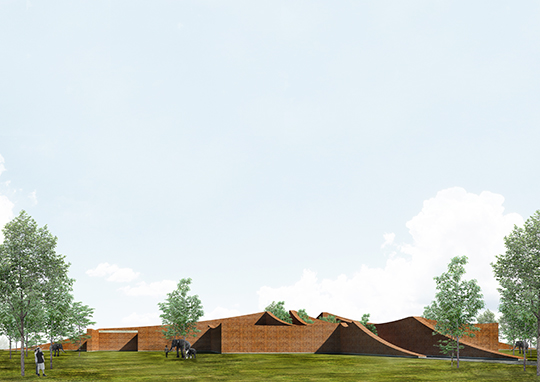

The site is located in rural area 52 kilometers north from the city of Surin, Thailand. I design the building to touch the ground ever so lightly to minimize the interruption of Mother Earth. Almost like an elephant’s foot. The elephant museum a living museum. I imagine walking along the walls of the elephant museum, looking at my lost memory, seeing the children and elephants at play and thinking about our future. The observation tower, its structure ages beautifully with the weather. A transparent structure in various scale create different interior space of the building. At the same time, it will change the outside space. It is not a self-showcase building but it is a place for hospitality and relax. I design the elephant stadium like a home for both human and elephant. The house not only speaks of its self but also reflects to high luxury knowledge that related natural elephant’s home. It looks huge in scale but humble in form. Elephants feel free movement in large area like walking in a forest without a path. A poetic of terrain.

Elephants are the world’s largest land animal and the symbol of Thailand. The established bond between Thai people and elephants can be traced back to ancient times and still continues until today.

Ta Klang Village in Surin Province, adjacent to the 1,186-acre Dong Phu Din National Reserved Forest, has been a community of mahouts for over 360 years. Currently, there are 207 domesticated elephants in the village, which is the most densely populated area of domesticated elephants in Thailand and the world.

In this village of Kui people, where humans and elephants depend on and learn from one another from birth to death, elephants are respected and not viewed as animals or slaves that are forced to work. On the contrary, people believe that elephants are family members and treat them accordingly as if there were some kind of sacredness residing in them. Elephant raising is a cultural heritage that has been practiced from generation to generation.

A village where humans and elephants share the same roof is such a spectacle to beholders. The beautiful art of living of Kui people, known as the elephant raisers, is a good starting point to learn about ‘humanness’ and ‘animalness’ in order to preserve the uniqueness of this place, which is gradually disappearing, as a reminder that humans, self-proclaimed to be the most intelligent creatures on earth, cannot survive alone in this world.

The search for ‘humanness’ and ‘elephantness’ is, therefore, one of many ways to open up another dimension of boundless learning between architecture, landscape, environment, and science, all explained through art.

Elephants may be an indicator of nature, environment, climate, fertility, and cultural inheritance.

The race for economic development results in surging demand for land to grow cash crops, and thereby the invasion of the Dong Phu Din National Reserved Forest, the Dong Sai Tho National Reserved Forest, and the lowland floodplain forests of Wang Talu, all of which were once a fertile stretch of land with vegetation that served as food and medicine for the elephants. With the shrinkage of these areas came the shortage of natural resources to the point that domesticated elephants did not have enough to feed on, and the mahouts, or the owners of the elephants, were deprived of their stable income. As a result, they took the elephants to work at elephant camps. Some traveled to cities with their elephants to make a living, wandering the streets of Bangkok and other touristy towns to sell souvenirs and elephant food so that tourists could feed the elephants with that very food items they sold. This situation detrimentally affects the respected status of the elephants and their health, as well as creating social and family problems of the mahouts who had to leave their home for a long time, traffic problems in cities, including a negative image of Thailand. For working elephants in tourism, they only have short-term contracts and without any protection or welfare for themselves and their mahouts. In addition, a lack of unity in the problem-solving effort among relevant government bodies worsens the problem as they prioritize other tasks over the elephants. As long as the problem persists, the elephant population will only keep declining and may eventually become extinct.

In 2015, the “Elephant Learning Center” project was established on over 1,186 acres of land in the Dong Phu Din National Reserved Forest next to the elephant village, financed by the government to conserve the elephants and the Kui community as a cultural learning center and a nature conservation learning center. The project also aims at conserving the environment, creating jobs, income, and opportunities for people in remote areas so that they can be self-subsistent after having been living in poverty for the entire time. This project will, therefore, be like a home for the elephants. It consists of Elephant Playground, Observatory Tower, Elephant Museum, a shop for community products, a café, and other buildings. The construction began in 2018 with some parts approaching their completion and some still under construction. When the project is completed, it will be a solution to those stray elephants in cities by bringing them back to their home with a promise of new jobs. It will help promote cultural tourism of the area, restore the Dong Phu Din National Forest to be as fertile as before, and establish government-approved standards for a systematic elephant protection.

The buildings in the project reflect the “commonplace” of their surroundings, originally created by the villagers who are non-architects. After pondering upon ‘humanness’ and ‘elephantness,’ we found that the existing buildings were not truly built for elephants but for humans. Therefore, we tried to integrate the scale of the animal which is larger than humans into our architecture as can be seen in the Playground building (The Life). The Playground features an enormous mundane gable roof over a hill transformed into a seating area. The simplicity of the roof and the hill is a convergence of beauty achieved without too much effort. The Observatory Tower (The Landscape) was created as part of the landscape for humans to absorb the beauty of the plateau, land, a rural way of life, rice fields, hills, villages, temples, an elephant cemetery, forests, roads, reservoirs, people, and elephants. It is a vertical building that slows down people’s movement with alternate staircases between each floor and openings of many sizes in the wall structure. The openings on some floor are large enough for people to see outside while some floors only allow thin rays of light to penetrate, creating a dynamic interior atmosphere throughout the day. The Museum (The Time) is designed to be a natural classroom for humans to be aware of the elephant’s scale through thick brick walls which give off a sense of strength and horizontally blend with the hills. Inside the Museum which tells stories of elephants and Kui people, only natural soft light is allowed to come through the roof, creating a peaceful atmosphere to convey the emotions of elephants that are gentle and friendly to humans. Stories told by youths in the area illustrate the unedited truth that makes this museum natural and timelessly alive. It also encourages the local to search for the value within their own community.

These buildings have become a symbol of the stories and lives of the people and the elephants living in the area, and a reflection of a rustic life and resilience in the face of global changes.

Philosophy of the non-human

Since the past, humans have put themselves at the center of everything. It’s time we listen to the “sound” of non-human lives that speak to us. By reducing anthropocentric thinking, we may become more human.

The Kui village reflects the bond between people, elephants, and forests. Reforestation means an increase in food sources, a call for the elephants to come homes, a promise of enough food, water, medicine, and work, a source of income to feed the families of not only the elephants and mahouts but also the community. At this village, there are a construction method that takes into account the elephants, village rules based on the practices of elephant domestication, a common language for humans and elephants, a leadership by elephant whisperers, and an economic growth that depends mainly on elephants. For these reasons, the Kui village is an elephant village inside and out.

The Kui way of life is worthy of praise for propagating the elephant culture that has been practiced since ancient times. It is an example of how humans learn to understand the philosophy of the non-human, which is a rare thing to see on this planet. Perhaps, by learning the nature of animals, we may understand more about what it is to be human. Architecture is a result of this contemplation of how we all can live together more happily in today’s world.

Senses of Elephant

Non-architect language

ELEPHANT PLAYGROUND

BRICK TOWER

ELEPHANT MUSEUM

SHOP

BOX OFFICE